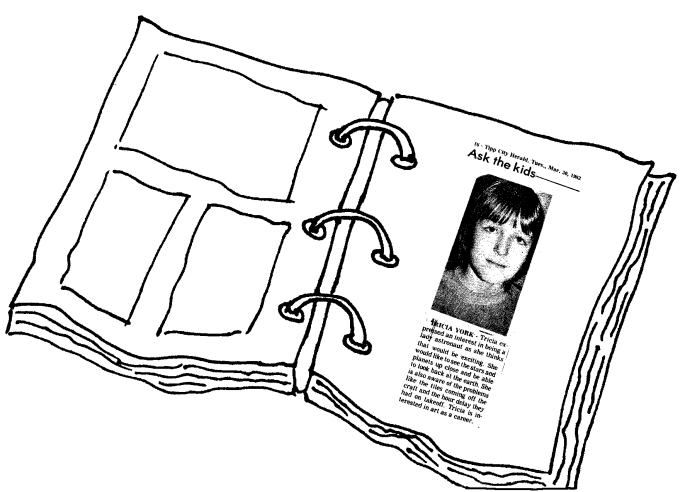

Hi, from the spacey kid.

In 3rd grade, I declared my intention to be an artist… if astronaut didn’t work out. I’m the artsy kid who found engineering, thankful that design has transformed STEM into STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, Mathematics).

I’m a holistic, multidisciplinary designer. I value every phase from user research through implementation — and enjoying coaching and contributing to each one.

My career trajectory has been about helping people to comprehend better, faster, and more delightfully in many media. Needless complexity moves me to action, as does a lack of emotional connection. Bring on the beauty, whimsy, and authenticity!

I’m an open book (pun intended ^).

I’ve answered some popular UX interview questions in these categories.

- Overview // design background

- Street cred // design savvy

- Viewpoint // design perspective

- Design is made out of people! // research

- On the playground // teamwork

- Sticky situations // challenges

- Strictly business // business savvy

- Tales from space // a few projects

Overview

How did you get into design?

From age 4, I loved to make tiny, intricate 3-D paper furniture, as well as “tack” for my horse models. Mom encouraged me to draw and to sew. My middle school offered an art class, showing me it can be a career. In high school, I found engineering and business.

When you’re a teen planning your entire life, choices invite angst. College was a crossroads between engineering and my thirst for arts & humanities. I chose advertising management in Ohio University’s journalism school due to its enticing combination of business, graphic design and copywriting, plus endless arts & humanities. Math counted as a language!

After graduation, I moved to NC and began working for an ad agency. I started those engineering courses I missed. Luck or fate put the IBM recruiting booth next my agency’s booth at a career fair. Preparation got me the job with IBM, as a writer who could code!

As a technical writer, I couldn’t help but to obsess with our web site user experience, wondering why we couldn’t transform our rich XML content to better meet user needs for personalization, customization, and interactivity. That led me to become the team’s information architect when IBM introduced that role in 2003.

For seven years, I practiced various design skills. An astute manager saw that my web design skills were transferrable to software design and invited me to make a career shift. Six years later, IBM appointed me to Design Principal in 2016.

I love being a professional designer addressing complex business and delivery challenges to make a difference for humans interacting with our software. It seems like design has been in my heart all along.

What are your design principles?

I wish my core principles were sexier. A little showmanship, mostly substance…

Focus. My favorite design advice is from Stephen Few, who says to remove any pixel that doesn’t add informational value to a dashboard. Emotional connection can have value, too. Culturally, focus means picking a few things at a time to do well.

Visionary, holistic experiences. It might be obvious to designers and to consumers. Our challenge is to keep imparting it to business leaders and engineers. Innovative user experiences enable companies to leapfrog competitors and disrupt markets. A product trying to catch up with feature parity is way behind.

Design Thinking, democracy, and apple pie. I truly believe that diverse teams align, decide, act, and win faster. Whether it’s voiced as agile methodology, design thinking, the multiplier effect, kaizen, or pixels pulling their weight… I’m sold.

Decisiveness and momentum. Approximate computing is an emerging field that focuses on finding the threshold at which to seize the approximate answer from the data, instead of awaiting the perfect answer. On that note, I’m comfortable making decisions after piecing together and analyzing the available data, as long as it meets the basic threshold. Being in motion provides new data, insights, course-correction opportunities, and adjacent paths to take (where innovation happens).

What are you looking for in your career?

Beyond the table stakes (financial security, balance, high morale), it’d be:

- To impact quality of life

- To work on problems important to humanity

- To have maximum business impact (design involved early)

- To be an expert on a dream team of existing and emerging experts

- To grow and learn from colleagues, especially early career

- To contribute to a vibrant design community

- To propel winning products

- To learn continuously

Street cred

What is your design process?

- Frame the problem (user research and “who, what, wow”)

- Work with the team to posit a solution (diverge, converge, low fidelity)

- Iteratively make and validate the solution (prototyping, high fidelity visuals)

- Harden it into excellence before delivering (only one chance for a first impression)

In reality, a designer has to be ready to parachute into any step. My process is quick, flexible, and action-oriented with ongoing validation. If it’s an existing UI redesign, I like to decompose it to the conceptual level (problem statement) and rebuild it.

What tools do you use?

Whatever works — the approach with the lowest fidelity and highest efficiency afforded by the audience requirements. I’m flexible, practical, and team-oriented because sharing and reuse matter. Specific highlights, in alphabetical order:

- Balsamiq

- Pen and paper

- Photoshop

- Prototyping (Java, HTML, CSS, Eclipse IDE, bug systems)

- Microsoft Office, and its Google and Mac counterparts

- Mural

- Sketch (a little)

- Ziggy cam

How do you define design, in laymen’s terms?

The textbook definition of design is the intention behind an artifact. Think of a time you were disappointed or annoyed because it seemed that little thought had gone into something you were using. You observed, “Clearly, they don’t know me at all” or “Obviously, this is intended for someone else.” That’s a design problem.

Imagine your challenge is to design a home.

A lead or UX designer is like the general contractor, ensuring everything fits together into a cohesive and delightful experience for the homeowner. The home must be technically feasible to build and meet business conditions that suggest it’s marketable.

A design researcher provides data about what kind of home the homeowners would like to live in (“generative research”), as well as making sure that a specific home plan meets the homeowner’s needs (“evaluative research”).

An information architect is concerned about whether the home has the right rooms, that each room conveys a clear purpose, and that the homeowner navigates smoothly among rooms. Door and hallway placement matter.

An interaction designer ensures that every door handle and light switch is in a sensible location for the homeowner (for example). He or she strives for the homeowner to interact naturally with the home’s voice and touch controls.

A visual designer often is thought of as a decorator, but is responsible for so much more. An emotional connection makes the house feel like a home, through architectural details such as door and window shape: Arched or squared off? Decorative or simple? Painted to draw focus, or to blend in? The home reflects the builder’s brand and the owner’s style.

Accessibility is an overarching design concern — why limit who can comfortably live in or visit the home? Anticipate special needs involving mobility, sight, and other factors.

What is your design speciality?

- 13 years of interaction design experience (daily use)

- 13 years of user research experience (sporadic use)

- 7 years of content experience (daily use)

- 6 years of visual design experience (frequent use)

- Coding projects to maintain skills (catch-as-catch-can)

What is “usability” versus “user experience”?

Usability involves ease of use, often focusing on the user interface. Outcomes are measured by task performance, such as reducing the number of steps to reach a goal.

User experience involves meaningful connection, encompassing all aspects of the user’s interaction with a brand and its products. Outcomes are measured by sentiment reflected by questions such as, “How likely are you to recommend it to a friend?”

Viewpoint

How do you stay current on design?

- Social media

- Professional associations (AIGA, UXPA) and colleagues

- Magazines such as Wired, Architectural Digest, and In Style

- Local museum and art events

- Pop culture

Who inspires you?

I’m most inspired by ideas and data, compared to having heroes. I cast a wide net for inspiration because a fresh outlook can come from anyone. By scanning a smattering of sources on a regular basis, I pick up on visual and societal trends and enjoy thinking about their intersection, which is a rich source of innovation.

If forced to name some people, I’ll be giving some dull answers:

- User experience: Don Norman

- Data visualization: Stephen Few, David McCandless

- Storytelling: Coen brothers, Malcolm Gladwell

- Visual arts: Barbara Kruger

What are your favorite objects?

My favorite object right now is my Jeep Wrangler Unlimited.

Minimalist: Since 1941, the recipe has been to “Keep it Simple.” In a world prone to over-engineering, the restraint is refreshing. The body design has managed to remain both current and iconic throughout several decades. It’s amazing, really.

Well-designed: With the exception of a few “Easter eggs” included purely for fun, such as a tiny Jeep climbing a hill in one corner of the windshield, every detail seems perfected for its purpose. For example, the bin in the top center of the dashboard has grooves that help to keep my cell phone (GPS device) standing upright.

Versatile: It’s a convertible with several modes to suit the weather. It seats four people as comfortably as a sedan. I can haul my dogs and cargo as I would with an SUV. I can pull a trailer or use it winch another vehicle, as I would with a truck.

Individual: It has standardized customization points, anticipating modification with products from its extensive third party ecosystem. I found it super easy to install a trunk box and different side mirrors for when I remove the doors in the summer.

What are your favorite apps?

- Instagram: Does just a few things well, and simply. Encourages creativity

- Simplisafe: Isn’t creepy like many home security brands. Makes DIY feasible

- Houzz: Combines many powerful capabilities seamlessly for each target user

Which app or site drives you crazy?

iTunes drives me mildly crazy:

- The information architecture is too flat and crowded

- The visual design is pretty but sprawling. I have no idea where to focus

- The interaction design is governed by mysterious rules, especially for updates

- The brand conveys it’s about Apple, not me… my dearest content is buried deep

I’d fix it by starting from the end user perspective, despite its content selling objectives.

What’s the next big thing in design?

I like to scan the horizon, but tech changes so fast, I rarely speculate far ahead.

The 2016 Consumer Electronics Show underlined “tech that disappears.” This made me giggle a little because it seems obvious to a designer. Specifically, the CES headline was about showcasing voice control in home automation, giving homeowners a really natural way to master their smart refrigerators and other devices in the Internet of Things (IoT).

I’m also excited about material design standards that let designers gleefully and coherently mix multiple media, such as line art illustrations, slick graphic design, and realistic representation of real-world items (skeuomorphic design).

I’m fond of a Tamogothchi touch, which endears an app to its user by having the user tend to the app. I like the concept that not every interaction in an app must serve a practical purpose. Some interactions create emotional connection, which has a different payoff than achieving a goal.

For example, I enjoyed an iPhone app that had me tap the screen to feed the lovely fish in my imaginary Koi pond. I could see making a B2B app more friendly and light with a well-thought Tamogotchi feature. Interstitial and error screens are a similar opportunity to add some personality via what I’ve heard called “micro-copy.”

Design is made out of people!

How do you know a design is tailored for users?

- Keeping up with social science and studies will get you in the right ballpark

- Using design thinking methods for a project puts the focus on the human experience

- Generative research provides data to validate market and user needs

- Evaluative research provides data to validate meeting user needs as expected

- Net Promoter Score provides the ultimate proof: Would a user recommend it?

How did user research change your design?

User research always informs my design approach. It seems risky to to design a user experience for someone you’ve never met, just as it seems risky to create a product for a market whose problems you don’t really understand.

That said, I’m comfortable making and acting on decisions based on incomplete or imperfect data, beyond a threshold. Tradeoffs between data and risk are part of business.

Here’s a specific example of how user research changed my design…

As an information architect, I performed user and competitive research to rethink my web site design, such that clients called the navigation “vastly improved” and said that they didn’t need to search because the site organization was so intuitive (high praise!).

To make the transformation, I compiled feedback trends from a database I’d started for the team a few years prior. I researched competitor web sites and tapped into Subject Matter Expert knowledge, forming cross-functional teams to redesign the navigation. I stepped back to differentiate user experiences for beginners, novices, and advanced visitors. I validated the updated design with users at key clients.

Of what generative research are you most proud?

A research team had been meeting with a client’s stakeholders for about two years, compiling 40+ pages of copious interview notes — several dozen ways that various city departments envisioned empowering their business users with analytics.

The client CIO’s patience was waning. The research team enlisted our product development team to make it real. I was to design the framework ASAP, but couldn’t conduct any new research with end users. The time for talk was over!

Although I didn’t conduct the interviews, I know that my analysis and application of the raw notes was vital to the project’s success. My team was only able to design an easy to use, flexible, and extensible analytic framework only by understanding the breadth of needs for the user experience. See Work for a more detailed recap of “City Analytics.”

Of what evaluative research are you most proud?

We wanted to find out what it would take to repurpose the city analytics software (see preceding question) for private real estate investment. I convinced the client and my managers that a usability test would yield good data.

In just two weeks time, I planned and led in-person, scenario-based usability testing with 5 target users, plus some adjacent users suggested by the client.

For the testing session, I enlisted help recording why or why not users completed each step, and whether they needed hints. I collated results into a spreadsheet. I came up with a color-coded shorthand to show the client executive and my managers — viscerally — where this new set of users became confused.

My project team and the client were able to focus on where to triage the existing analytics to suit the real estate investment users (after deciding the pitfalls were surmountable).

On the playground

What’s your communication style?

I try to listen closely, empathize, and be aware of the audience.

- Designers – express collaboration; exchange learning; focus on the human problem

- Engineers – communicate precisely; know some programming

- Product managers – tell a story; focus on business value, human experience, MVP

- Project managers – show awareness of deadlines; enlist their help (reminders, etc.)

- Executives – tell a story; back it up with data; keep points brief and visually polished

- Clients – listen more than you talk; draw a roadmap; never argue in front of them

How would teammates describe you?

- Creative, fresh perspective, challenges team with ideas

- Visually astute, detailed // politely demanding of Front End Developers

- Intelligent, analytical, and curious // encourages us to do our research

- Gets things done, self starter // can seem impatient

- Good listener, detailed note taker

Upon request, I can share quotations from recommendation letters for Design Principal.

Do you prefer to work alone, or on a team?

Throughout the day, and depending on the task, I’ll do either one. Like most people, I value blocks of quiet time to think deeply and reflect. I sit in an open studio space, but sometimes work at home to save gas and see my doggies. I like the camaraderie of the design community, as well as being part of an agile development team.

How do you give and receive feedback?

When giving feedback, I aim to:

- Be kind but honest

- Subtly use the sandwich method (praise > room for improvement > praise)

- Cite data and principles to avoid it seeming personal

When receiving feedback, I aim to:

- React with humility, inviting further feedback

- Avoid taking it personally, or let it go

- Learn from it

Sticky situations

What’s your biggest or favorite design challenge?

My most invigorating (but feasible) design challenges are:

- Learning a new industry and its users (method acting!)

- Figuring out how to visualize data and processes clearly (so fun!)

The practical challenges I regularly must overcome as a designer include:

- Obtaining access to end users

- Tuning into end users, while hearing out any other vocal stakeholders

- Providing end users with an experience that pushes beyond their comfort zone in a positive way (a locomotive they unexpectedly love, as opposed to a faster stagecoach)

- Being included proactively instead of reactively by business leaders on my team

- Tactfully pointing out when a creaky technical platform needs to be updated

How do you handle conflict?

1) Like most human beings today, I believe in win-win negotiation. Resolving conflict is about empathy and finding common ground, rather than “winning” over an opponent. Seek what you agree upon. Defuse emotions, without dismissing deeply held values.

2) Conflict isn’t all bad. In fact, it’s what makes for a meaningful meeting, according to Death by Meeting. The book suggests resolving everything you can before the meeting, crisply defining the remaining points of conflict, and then meeting to address them.

3) In designing software, IDEO’s Tim Brown inspires my teams to find technical solutions that have a market, are technically feasible, and that offer delightful user experiences. In practice, this requires a fairly radical culture change when teams aren’t accustomed to business, engineering, and design leaders collaborating concurrently.

What if the client rejects your design?

I really want to establish a relationship with the client before any conflict arises.

If conflict does arise, then I really listen to the issue.

- If it’s a mistake, I’ll own it and fix it.

- If it’s a communication problem, I’ll see if clarification helps.

- If it’s a difference of opinion, I’ll persuade with expertise and data.

Ultimately, if it’s a project for an individual client, I have to meet the client’s user needs. If it’s a product, I have to consult multiple “sponsor clients” to ensure the end result is marketable (not bespoke).

What if someone refuses to budge on a design?

- I listen carefully to what this person is saying, and why (their perspective)

- I look at user research, studies and norms in design

- I try to focus us on the end user’s problem and needs, not on pet solutions

- I hope I’ve already established a foundation of trust with that colleague

- I hope I’ve already established myself as a design expert

- Ultimately, I consider whether I own the design… I’m responsible

- I consider whether the account is a singular client or we’re making a product

What if a bunch of people won’t agree?

This happened on a project to create a way for city leaders to have real-time status. My development team was working with a “sponsor user” organization we hoped would become the reference account for winning additional business.

The Engineering executive recently had seen a traditional but slick third-party dashboard. He strongly encouraged the design team to recreate that experience for the client (or he’d hire the third-party firm to do so). In contrast, the Design executive told us to break and remake the user experience of a “dashboard.”

I stood between the two. I supported innovation, as long as we didn’t take it way beyond the client’s comfort zone or comprehension. Four more designers were involved, each of us with a different perspective, and somewhat influenced by our respective bosses.

I called a “Design Blitz” in which we each came up with a concept car. I had us present our concept cars to the executives and then to the client, asking for likes and dislikes about each concept car, and why.

This approach refocused the project team (including executives) on the user needs, taking great ideas from each design, as opposed advocating entire designs as winners or losers. With this new insight, the designers united and we got it done.

Who makes or owns standards?

Design standards exist to meet user needs. We must never lose sight of that. In any somewhat large organization, design conventions will exist at several levels because products ship — there’s no awaiting a top-down edict. Furthermore, a natural tension exists betweens standards and new innovation.

Ideally, the various teams are proactively working to bring their home-grown standards into alignment with one another and with top-level brand guidelines for the sake of the users, their companies, and our company.

What if an engineer says, “It can’t be done”?

- Before conflict occurs, I want to earn street cred by understanding the code.

- When an engineer says it can’t be done, I’ll listen carefully to identify the issue.

- If I believe it can be done, I’ll make a case after delving into the technology.

- I’ll try to show the user’s problems to encourage empathy and problem-solving.

- I’ll cite UX research as to why it should be done the way that I propose.

- I’ll try to refocus the engineer on user needs (versus his or her pet solutions).

- I’ll allow some time and be encouraging — engineers generally want to solve problems and do right by users. It can be a matter of giving them time to think.

What if many projects have the same deadline?

This is business as usual… I have lots of experience juggling design for various projects. Work ebbs and flows. You just have to rise to the demand.

To avoid crunches, projects can define a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) up front so that the end goal is clear. That is, the team knows when it’s done.

It’s much more challenging to juggle multiple projects whose goal is to implement as many features as possible before the product deadline. There is no done.

How do you handle change?

Change is inevitable. You have to stay chill and prepare to course-correct.

Reactively, try to understand the reason for the change. Why did it happen? How do we adapt to it? Can we avoid it next time? What can we learn?

Proactively, rally the team (engineering, business, and design) to aim the project at the right goal through market and user research and defining Minimum Viable Product (MVP). During the project, communicate and align continuously.

Long term, the organizational structure and team personalities should be adjusted to minimize the need for change and to maximize its adaptability to change.

Strictly business

How to balance user needs and business goals?

Tim Brown (IDEO) spoke of design thinking as a way “to match people’s needs with what is technically feasible and a viable business strategy.” Sounds like a Venn diagram to me. In practical terms, design thinking teams need their designers, engineers, and offering managers to triangulate the sweet spot at which the three rings overlap. Also:

- Engage multiple sponsor clients to spread risk (again, more circles => better focus)

- Ensure that the users with whom you collaborate are representative of markets

- Don’t let other stakeholders dominate and skew the design input

How to decide which features go in a release?

The worst answer is “As many as we can finish before the release date.” I much prefer to use the IBM Design Thinking approach of focusing on a few user experiences to deliver really well. The Minimum Viable Product (MVP) release content consists of 3 “hills,” at which the team arrives via design workshops. A hill pinpoints:

- Who (human being, typically by user role)

- What (goal for the experience)

- Wow (competitive advantage)

How do you know when the design is done?

- Do your market and user research to support truly fact-based decision making

- Early on, define an Minimum Viable Product (MVP) and “hills” with design thinking

- Prior to the release date, validate and course-correct the design continually

- Near release, evaluate if MVP has been reached (consider an Andon cord approach)

- After release, collect Net Promoter Score and other feedback

Tales from space

Which recent project makes you most proud?

The IBM Intelligent Transportation project involved consolidating and modernizing the workings of an American traffic authority, then generalizing the solution into an application for managing roadways with cutting-edge operational views and analytics.

The business opportunity was to earn a critical reference client. The human opportunity was to play a major role daily in keeping thousands of travelers safe on highways.

The team included the client, our software product development team, a client services team, and a business partner.

The biggest design challenge was to discern and apply the opinions of the end users from that of the other (very vocal and high-ranking) stakeholders. I held meetings with all to co-design the solution, then followed up individually with end users to make sure I was hearing their specific needs and wants.

My design approach included contextual inquiry (shadowing the end users), producing life-size UI mockups to help the users understand how much data would fit in the GUI (they were accustomed to a concise set of “green screens”), and leading regular meetings to “play back” the design and obtain stakeholder input.

The outcome was positive — the client CIO remarked that my design leadership helped the organization to make its business and technical transformation. The end users adopted the solution, with some hiccups that I wish I’d prevented with even closer collaboration with them.

The client is using the solution today. A generalized design went into the shipped product, which is still being licensed to various other companies.

Which recent project was a challenge?

The project was to develop an application for insurance companies and similar clients to analyze their data for unusual patterns possibly pointing to fraud.

The business opportunity was to earn a reference client by working with a big insurance company as a sponsor user. The human opportunity was to drive down insurance premium costs by identifying bad actors, not to mention making analysts’ jobs easier.

The team included the client, our development team, and another software development team for the base product (think platform) on which we’d build our application.

The biggest design challenge wasn’t driven by client needs, but involved building our application atop a base product. Some leaders in the base product team seemed to prioritize defending its existing architecture (database schema) over helping us to meet the user needs for our application.

One particular architect was a bully. My teammates would admit to me, but not to him, that they didn’t fully understand how to apply his architecture. Whenever the team would meet with him, he’d berate me as the only person who brought to light the need for architecture updates to meet our needs. My team would be silent.

My approach centered on drawing together our application team (business, engineering, and design) to imagine a design that met our specific end user needs, independent from the limitations prescribed by the base architecture. We united to do what was right for our users, including validating it with the sponsor client. This helped to build the conviction that my teammates needed to stand up to the bully architect. I told him that this was the Minimum Viable Product design as determined by our team.

The outcome was that the right design for users is being implemented, although it’s taking more iterations than were scheduled. The business okayed that decision.

I learned to stick to my guns when the alternative is to deliver something less than Minimum Viable Product — something that meets neither our user needs nor our business objectives — especially when no one else will. The sky won’t fall.

I’ve rarely had to put my foot down that way, but now I know that I can. It complements my usual “catch more flies with honey” approach, as described by a former manager: “Trish has done a wonderful job in helping the projects to be successful by providing useful, tangible deliverables that development can use, collaborating with the teams about what can be realistically achieved.”

Which project feels like you failed?

The project was to create a toolkit to enable software solution subject matter experts to document bespoke solutions (comprised of multiple products) for their clients. Solution SMEs were the only authorities on what comprised a specific client’s solution.

The business opportunity was to solve a Big Hairy Audacious Goal (BHAG) for IBM clients. The human outcome was to benefit thousands of client end users.

The team included product information subject matter experts representing literally hundreds of IBM products, client solution subject matter experts, and our Software Group Architecture Board incubator team (which funded projects to try out new ideas).

The challenge was in the sheer number of internal organizations representing the stakeholders (22 in total). I recruited and led representatives from each organization. We collaborated to find a solution based in “user research” of their respective organizations’ needs for authoring tools for client-facing solution subject matter experts.

My approach was to act as a product manager, gathering their feature requirements (this predated IBM’s adoption of Design Thinking). As my development team created a toolkit for client solution SMEs to document bespoke solutions, we held usability tests and a pilot program to validate the tool. User research informed the information architecture of solution information navigation and page content templates that shipped with the toolkit.

The outcome of my workgroup included:

- Handing off 60 solution information recommendations to 15 organizations

- Releasing standards for 4400+ product information developers

- Releasing a toolkit for 25,000+ solution subject matter experts

- Having 50 toolkit downloads in 9 global geographies

The last statistic made me feel like a failure because of the ratio to actual downloads versus the potential audience. I learned the pitfalls of collecting and delivering many mundane user requirements, as opposed to focusing on a few game-changing user experiences. I realize how difficult it is to be a product/offering manager using a requirements laundry list approach.

I also realized that many potential “sponsor clients” are willing to give you requirements, but this doesn’t necessarily translate to adoption. In fact, I had one such user remark that he gave me feedback because I asked for feedback, not whether he’d ultimately adopt the tool (which he had no intention of doing so). For this reason, I find the deeper client relationships formed via IBM Design Thinking to be especially valuable.

The silver lining is that my workgroup’s recommendations and standards had a wide organizational impact. I take solace that I formed the first-ever workgroup to cross organizational lines between product information producers and client solution subject matter experts because I saw an unmet client need we needed to address.